Happy 60th Birthday, Mom.

I love you more than I am scared of heights.

So impressed you hiked Half Dome at 60.

Half Dome at 60: My Mom’s Lesson in Blue-Collar Humanism

My childhood best friend once said, “The one thing you need to know about Janet is that she would wake up to go to a 5 a.m. swim workout.”

I disagree. There are several dozen people in the pool at 5 a.m. The one thing you need to know about my mom is how cheap, creative, and hardworking she is. In a world where you can order anything on demand, she still uses the proverbial full buffalo. For example, if she saw fresh roadkill on her way back from swimming that hadn’t been there at 4:30 a.m. on the way in, she’d pick it up and dissect it for her anatomy class. Roadkill is cheaper—and more interesting—than ordering frogs. To my mom, there was no line between public school biology and raw intellectual curiosity. She believed every kid deserved hands-on science—even if it meant hauling a squirrel off the road in a Honda Fit.

Her love of teaching science spans decades. A couple of years ago, one of her high school students was published in Nature. Published in Nature while still in high school. When she started teaching at Dublin High, no students entered the science fair. When she was working full time, one in six did. Some worked on projects for years, won scholarships, and got published. Occasionally, I even heard about it at the dinner table.

As a kid, you’re on the inside looking out. Then you grow up, move away to a new town or state, and find yourself on the outside looking in. That’s when you realize what makes your family different. What makes my mom different is that she lives by a philosophy I call blue-collar humanism.

Blue-collar humanism is a grounded, quietly radical belief that dignity, meaning, and genius aren’t reserved for ivory towers—they’re forged in daily effort, working hands, and fierce love. It’s not something you’ll find in most philosophy books, but it’s how she raised us – and probably why Taylor Sheridan’s stories like Yellowstone and Tulsa King make me cry.

And it’s a philosophy that celebrates birthdays with hard things. Why hard things? A form of existentialism, I think—feeling alive through struggle and choice. To my mom, effort isn’t a virtue to be rewarded—it is how you pay rent on the life you want.

At 40, she hiked Half Dome with me. At 45, she swam a 10k. At 50, a 5k. At 55, it was Covid. Nothing happened. At 60, she hiked Half Dome again—this time with me and my brother.

This most recent hike was much harder for me than it was twenty years ago. In that time, I’ve developed new fears—including a fear of heights.

According to the National Park Service Website, “The 14- to 16-mile round-trip hike to Half Dome is not for you if you’re out of shape or unprepared.”

Our mom made sure we were prepared. She had us make our own sandwiches—no fancy hiking snacks, just peanut butter and jelly. Her approach to hiking was like her approach to teaching: no corners cut, no excuses, everything earned. She made fun of me for walking seven miles in new heels two days before the hike. My brother—who has fought fires, trained army recruits, and now DJs—had just walked 100 miles at a music festival and had a cold. She made fun of him too.

Neither of us wanted to let our 60-year-old mom beat us.

While some hikers may have new bags. We packed everything into old bags my mom carefully stored for decades. One was my middle school backpack covered in pink flowers. The strap broke. “Thank goodness” she exclaimed. “I can finally throw that away”.

I tried to convince my big strong little brother to carry everyone’s water up the hill. The idea was rejected by both my mom and him. Everyone was fit enough to carry their own water.

We left before dawn. Coffee. Road. Park by 6:30. Trail by sunrise. If you’ve hiked Half Dome, you know there are three parts: stairs up two waterfalls, meandering forest trail, and then the granite slab to the summit.

The steps up Vernal and Nevada Falls are carved into rock, slippery and steep. My brother teased me: “Jenny, I can train you.” I reminded him I lift weights twice a week. I’m just scared of heights, and those steps are slick.

After Nevada Falls, the trail flattens out. Poles help. Chocolate breaks every thirty minutes help. My brother skipping and singing? Not helpful to me but helpful to my mom’s morale.

Eventually, we met the ranger at the base of Sub Dome. Since 2010, you have needed a permit to hike the cables. My mom had entered the lottery. Of course she won.

We showed our permit. The ranger reminded us not to leave trash or fall off.

Then we climbed.

The carved granite steps to Sub Dome were easier than I remembered. I counted them to stay focused. 300 steps, I told myself. But after 300, the stairs ended. No cables. Just a steep, slick slab called Sub Dome.

Halfway up, my fear of heights took over. I felt dizzy and sat in the shade of a tree. My mom joined me.

“I don’t remember this,” she said.

The route had changed. It seemed more dangerous. A few other hikers joined us, all uncertain. One misstep and you could slide right off.

“We don’t have to go all the way,” she said. “This counts. I’m 60.”

We sat. Contemplated. Then a young family passed us on their way down. Maybe what my mom and I looked like twenty years ago. “You’re almost there. The cables are next. This is the hardest part.”

I love my mom more than I am scared of heights. I couldn’t let fear keep me at 80%.

One step at a time, I climbed.

At the cables, I sat for one last chocolate. Bobby was already halfway up. My mom followed.

I waited, wondering if I could do it. A woman named Amanda sat next to me. She was also scared of heights.

“My mom is 60,” I said. “She’s the one in bright pink.”

Amanda looked. “If she can do it, I can do it.”

So I stood up and followed.

The cables are hard but simple. Here’s what I recommend:

- Wear gloves. The metal ropes will shred your hands.

- Three points of contact. Always. You’re vertical crawling.

- Patience. Some folks freeze. Wait. Encourage them.

- Focus on the rock. Not the 5000 foot drop.

- Cheer people on. Ask where they’re from.

The cables weren’t just safety lines—they were reminders that every inch upward requires your full body, your full attention. It’s not elegant. It’s an effort. The kind of effort my mom has believed in all her life: not always graceful, but always honest.

At the summit, we ate lunch, took pictures, and soaked in the magic. Someone had proposed earlier that morning. The rock was surprisingly crowded—only 300 permits a day, but it felt full.

On the way down, everything felt lighter. Except my brother, who kept joking about California earthquakes and thunderstorms.

I put in an audiobook—Trillions, about ETFs. (Gross, I know. Still working on my blue-collar humanism.)

Coming down felt like flying, but only because my little brother made sure I carried my water up and it was gone on the way down. That’s the magic of blue-collar humanism: joy earned the long way.

At the bottom, we got more water. My mom was proud. I was a little less scared of heights, and a little more sure that work, in her hands, had always been a form of love.

Start of the hike.

Jenny, Mom, and Bobby eating lunch at the top of half dome.

Jenny and Mom were excited we did not slide off sub dome.

Me contemplating the cables. It was very steep.

Wear gloves!!! My gloves were shredded on the cables.

At this point Bobby was making fun of me for being scared of falling.

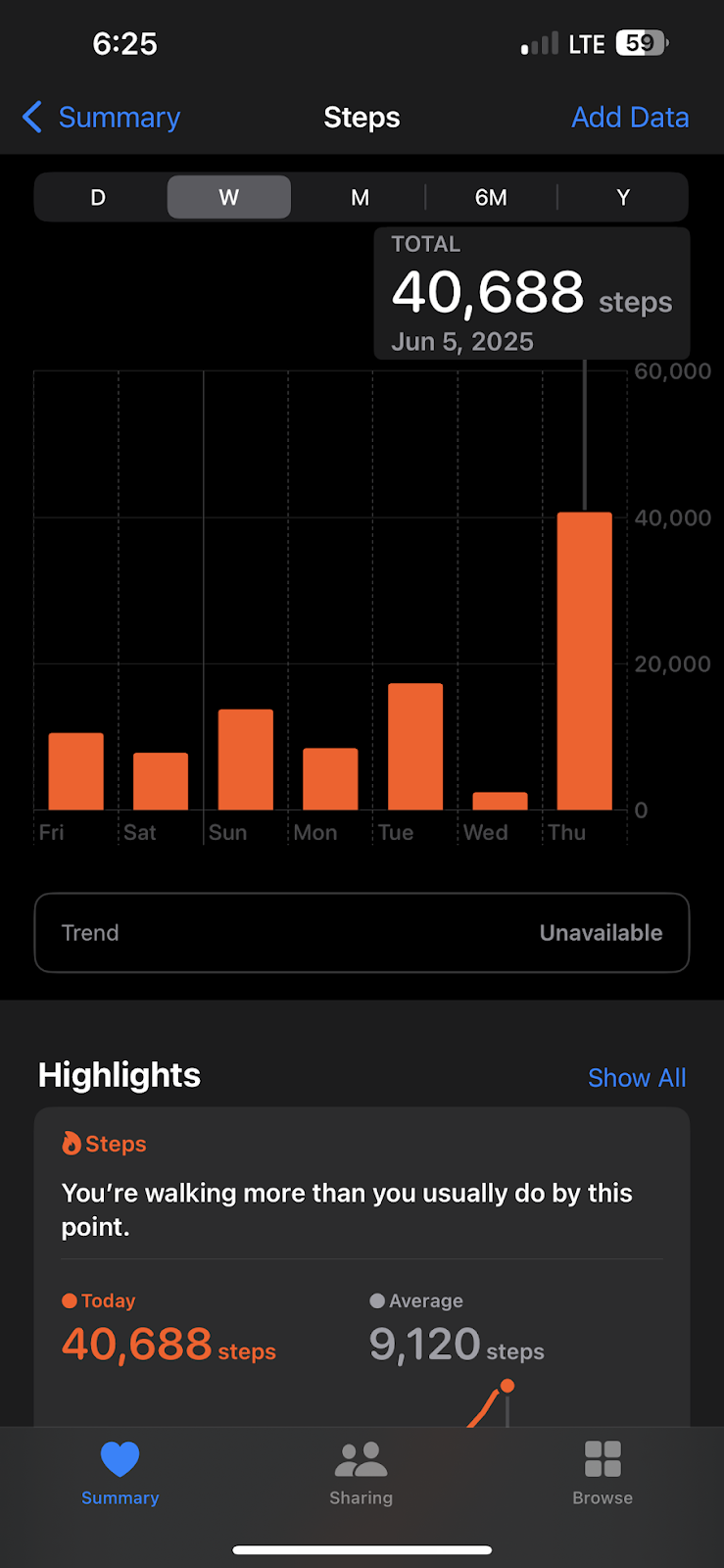

It was 40,688 steps up to half dome and back.

Follow me on LinkedIn, X, or Patron View for more.